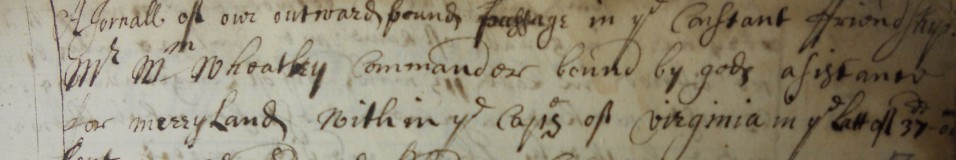

In my last post I discussed the importance of historical documents to my research, just prior to visiting Oxford to examine some ship logs from the seventeenth century. I was unsure of just what I would find, but what I found was more valuable than I had imagined. In the Bodleian Library at Oxford University I was able to access a logbook, written by a sailor called Edward Rhodes, dated to 1670-1676. This book was aboard four different ships in these years, crossing the Atlantic twelve times in all on six round trip voyages between London and the Chesapeake Bay, both to Maryland and Virginia.

On an average day, Rhodes mentions the wind, weather, and how far they traveled. Each day at sea, from making it past Plymouth and until reaching the capes of the Chesapeake Bay (or the other way around in the return direction), Rhodes gives the latitude and relative longitude of their position. Until now, we could only speculate on what the Northern passage across the Atlantic looked like, but now we can see exactly what course they took! Even more interestingly though, is that until the mid-eighteenth century, longitudinal calculations were based more on reckoning than actual position. That Rhodes was writing these down, and consistent in his end points, really shows that they were able to determine this with a degree of accuracy. London, or in the return the Bay, are always set to 0 degrees longitude, and the final entries are between 55 and 57 degrees. By today’s measurements, this should be around 75 degrees, but the consistency means that this error is manageable.

On a less than average day, Rhodes writes about the other events that occurred. On the First of January, 1672, he writes while anchored in St. Jerome’s Creek near St. Mary’s City, Maryland: ‘This day we buryed one of our Seamen Henry Miller.’ On the third of January, he writes: ‘we buryed one of our passengers named John Sippse.’ And two days later on the 5th of January, another entry: ‘We buryed our Second mate named Gabrill Hamon.’ One must wonder what has happened that caused these three deaths in such a short time. One other mention that I have seen thus far of a death on board was on another voyage from London, started in December 1672. They spent more than a month in London waiting for the right wind to get out of the River Thames. On the 5th of January 1673, a note appears in the side column saying: ‘We buryed one of our passengers ashore.’ Two horizontal lines separate this from an addendum: ‘a nigro.’ The log then states that ‘Being a sunday our (unknown word) departed this life att 4 in the morning. Then I went presently onshore and spoke for a grave for him…’ He goes on to write that he found a grave for him at a parish church, and describes what was payed for the services. Ten shillings in all. What this tells us though, is that a black man was traveling as a passenger on this ship from London to Virginia as a free man, and was of the Christian faith as he was buried at a parish church. This serves as a reminder that while race was clearly an issue at the time (otherwise it would have not been stated), it was not the only condition leading up to slavery. In the seventeenth century, slavery by the English was more a condition for those of a non-Christian faith. This shift is something I am not overly qualified to comment on, but occurs later in the 18th century.

Not all of the other special entries deal with death, however. Some of them describe events such as trade, or just something a bit special: ‘Today we caught a dolphyn.’ Of those dealing with trade, this is only mentioned in the 1671/72 voyage to ‘Merryland.’ Rhodes mentions that they sent the ship’s master ashore at St. Mary’s City to take care of customs. The next day they sailed for St. Jerome’s Creek, where the three men were lost. The log picks back up in late March, and mentions that they have now 550 hogsheads of tobacco aboard. They then sailed for St. Mary’s City and collected 160 more hogsheads. Specifically, it mentions the use of ‘Shalups,’ small tender boats brought along with the ship, to acquire the tobacco. I have heard in the past people describing the ships themselves pulling up to wharves, piers or landings at individual plantations to load the tobacco, but this is not what we see here. And archaeologically, we have not found any evidence wooden structures in the rivers dating to this time period. It seems that at this point of time, loading of the cargo was a task performed by the ship’s crew with the ship’s own tender vessels. Further, while a specific time is not mentioned to pick up the 160 hogsheads they load at St. Mary’s City, it is more than a month before it mentions that they leave the area with their load of 726 hogsheads to travel back to England. That this process took perhaps 25 days to complete just in the St. Mary’s River shows a total lack of centralization to the process.

Not all of the other special entries deal with death, however. Some of them describe events such as trade, or just something a bit special: ‘Today we caught a dolphyn.’ Of those dealing with trade, this is only mentioned in the 1671/72 voyage to ‘Merryland.’ Rhodes mentions that they sent the ship’s master ashore at St. Mary’s City to take care of customs. The next day they sailed for St. Jerome’s Creek, where the three men were lost. The log picks back up in late March, and mentions that they have now 550 hogsheads of tobacco aboard. They then sailed for St. Mary’s City and collected 160 more hogsheads. Specifically, it mentions the use of ‘Shalups,’ small tender boats brought along with the ship, to acquire the tobacco. I have heard in the past people describing the ships themselves pulling up to wharves, piers or landings at individual plantations to load the tobacco, but this is not what we see here. And archaeologically, we have not found any evidence wooden structures in the rivers dating to this time period. It seems that at this point of time, loading of the cargo was a task performed by the ship’s crew with the ship’s own tender vessels. Further, while a specific time is not mentioned to pick up the 160 hogsheads they load at St. Mary’s City, it is more than a month before it mentions that they leave the area with their load of 726 hogsheads to travel back to England. That this process took perhaps 25 days to complete just in the St. Mary’s River shows a total lack of centralization to the process.

I am now hoping to acquire more texts dating to different periods of the seventeenth century to gather comparative data, plot more routes, especially on the Southern passage, and perhaps better describe the cargoes that the ships are carrying. Further, following out this information on early calculation of longitude is an exciting and unexpected find that I hope I can elaborate on at a later date. A big thank you to Dr. Henry Miller of Historic St. Mary’s City, currently teaching in Oxford, for housing me while I scoured this document for several days!